In Vol. VI, The Reformation, of his monumental work, The Story of Civilization, Will Durant describes Marguerite d'Angoulême as "representative of two eras, The Renaissance and The Reformation". To my knowledge, no man has ever been so described by a historian. Perhaps Petrarch for the Renaissance. Luther for the Reformation. Voltaire for The Enlightenment. But no man for two eras.

Wife Esther directed me to her, having learned more about her in completing work for an M. A. in Comparative Literature at the U. of Maine (Orono) in 1971. Esther has compliled much material about her. I planned to help Esther create a website dedicated to this great woman, who seems so neglected by women here and abroad. With Esther's death, 12/22/00, I'm working this as a Memorial to my dear wife. In 2000, I obtained a French book (Jourda) about her from abebooks.com, which we've searched for over a 10 year period.

Margaret Of Angoulême, April 11, 1492, Angoulême, Fr. d. Dec. 21, 1549, Odos-Bigorre, also called MARGARET OF NAVARRE, French MARGUERITE D'ANGOULÊME, OR DE NAVARRE, Spanish MARGARITA DE ANGULEMA, OR DE NAVARRA, queen consort of Henry II of Navarre, who, as patron of Humanists and Reformers, and as an author in her own right, was one of the most outstanding figures of the French Renaissance.

Marguerite's father, Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême, was "direct descendant of Charles V ... in a position to claim the crown, in the unlikely-seeming event that both Charles VIII, and the presumptive heir, Louis, Duke of Orléans, failed to produce male offsrpring". In 1491, Charles married 15-year-old, Louise of Savoy, daughter of Marguerite of Bourbon, sister of the Duke of Beaujeu -- "dowry, a mere 35000 pounds... [but] one of the most brilliant femine minds in France". But Charles had fallen out of Royal favor in 1483, in politics involving the Regency of Charles VIII.

Mother named her "Marguerite" after her maternal grandmother, Marguerite of Bourbon. 2 years after birth, family moved (a little up river) from Angoulême to Cognac, "where the Italian influence reigned supreme, and where Boccaccio was looked upon as a little less than a god".

Marguerite's brother, Françis -- to become King Franc¸is I of France -- was born on Sept. 12, 1494 [Esther's birthday].

Marguerite's mind, thanks to mother Louise, had tutored since earliest childhood by excellent perceptors, prominant among whom was Robert Hurault, Abbott of Saint-Martin-d'Austan. It was under Hurault that Marguerite learned Latin; she read the Bible and Sophocles in the original. This young princess was to be called "the Maecenas to the learned ones of her brother's kingdom". In Dec., 1495, the frail little Dauphin died and, her father, the Count of Angoulême, was once more the second prince of the blood.

Mother, Louise of Savoy, became widow at 20, with daughter nearing 4, son past one, who was now (with his father's death) "heir presumptive to the throne of France". When Marguerite was 10, Louise tried to marry her to Prince of Wales, to become Henry VIII; but this was "declined with thanks".

Some one wrote of her that Marguerite needed to love more than to be loved. "Never", she wrote, "shall a man attain to the perfect love of God who has not loved to perfection some creature in this world."

Married at 17 to Charles, Duke of Alençon, 20, by decree of King Louis XI (who also arranged the marriage of his 10-year-old daughter, Claude, to François). This charming, intelligent, remarkably educated girl was forced to marry a generally kind, but possibly illiterate man for political expediency -- "the radiant young princess of the violet-blue eyes [ecce young Elizabeth Taylor]... had become the bride of a laggard and a dolt". Marguerite never loved her husband, the Duke of Alençon. Her marriage remained what it had been in the beginning, a simple business arrangement. She had been bartered to save Louis' royal pride, by keeping the County of Armagnac in the family.

Her mother-in-law, Marguerite of Lorraine, with whom as a collaborator in pious exercises and good works, the Princess was to form a close and fast friendship, and by whom she was to be greatly influenced in her religious views and activities."

Daughter of Charles de Valois-Orléans, comte d'Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy (then 15 years of age). The young Marguerite was a happy, slender girl with blue eyes and golden hair, distinguished even as a child. In her mid-twenties, she grew plump and her nose was too long. Yet she was still blue-eyed and fair-haired and kept her fascination.

King Louis XI invited Marguerite's family to lived in the Castke at Amboise. (Leonardo da Vinci later spent his last years, 1516-19) in the chateau Cloux outside this castle, as guest of King François I.) During their 10 year stay there, Louise engaged scholars -- Cop, Votable, Huralt, among others -- for the education of Marguerite and her younger brother, François, who became King of France. Under the tutelage of these capable scholars, Marguerite and François developed a deep love of learning, giving them a decided advantage over other members of the royal family.

King Louis XI invited Marguerite's family to lived in the Castke at Amboise. (Leonardo da Vinci later spent his last years, 1516-19) in the chateau Cloux outside this castle, as guest of King François I.) During their 10 year stay there, Louise engaged scholars -- Cop, Votable, Huralt, among others -- for the education of Marguerite and her younger brother, François, who became King of France. Under the tutelage of these capable scholars, Marguerite and François developed a deep love of learning, giving them a decided advantage over other members of the royal family.

In her book "Heptameron", Marguerite tells of her brother's first love-affaire. The fifteen-year-old François fell in love but the girl rejected him, even after continuing pressure. The girl then married someone of François's household and he continued to give the couple presents for many years.

Marguerite learned Spanish, Italian, Latin, Greek and some Hebrew. A lover of Petrarch, she also admired Dante. Above all, Marguerite enjoyed Boccaccio and had the 'Decameron' translated by her secretary.

Later, Marguerite's court at Nerac and at Pac became the most brilliant literary centers in Europe. This "radiant young princess of the violet-blue eyes" was widely loved and called "La Perla des Valois" -- the name "Margarita" means "pearl" in Latin. (In 1547, a collection of her poems was published under the title, Les marguerites de la marguerite de princesses: "pearls from the peal of princesses".)

Perhaps the one real love in her life was Gaston de Foix, nephew of King Louis XI. But Gaston went to Italy and died a hero at Ravenna, when the French defeated Spanish and Papal forces. Guillame Bonnivet fell deeply in love with Marguerite but found that she still loved Gaston. Bonnivet married one of Marguerite's ladies-in-waiting, just to be near her, and eventually also died a hero's death, in the Battle of Pavia (in which her brother, François was captured).

Marguerite became the most influential woman in France, with the exception of her mother, when her brother acceded to the crown as Françis I in 1515. Her salon became famously known as the "New Parnassus". The French renaissance poet, Pierre de Ronsard wrote of her

Te plaisent les douches herbes, Les fountaines et la fleur""The most beautiful and witty women of the age" was said of her -- a bit exaggerated as far as 'beauty' goes, but the 'wit' was appropriate. The writer, Pierre Brantôme, said of her: "She was a great princess. But in addition to all that, she was very kind, gentle, gracious, charitable, a great dispenser of alms and friendly to all." And of her Erasmus wrote: "For a long time I have cherished all the many excellent gifts that God bestowed upon you; prudence worth of a philosopher; chastity; moderation; piety; an invincible strength of soul, and a marvelous contempt for all the vanities of this world. Who could keep from admiring, in a great King's sister, such qualities as these, so rare even among the priests and monks?"

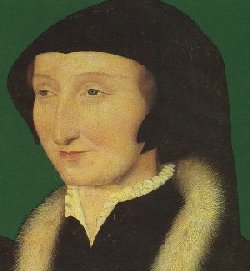

After the death of her first husband, Charles, duc d'Alençon, in 1525, Marguerite married Henry II of Navarre (Henry d'Albret). (Painting.) Although she bore Henry a daughter, Jeanne d'Albret (mother of the future Henry IV of France), the couple was soon estranged. Marguerite was, on the other hand, always devoted to her brother, François, and is credited with saving his life when he became ill in prison at Madrid after his capture at Pavia during the disastrous French expedition into Italy in 1525. The writer, Pierre Brantôme, said, "During the imprisonment of the King, her brother, [Marguerite] greatly aided her mother, Madame the Regent, in ruling the realm, in giving satisfaction to princes and the great, and in winning over the nobility; for she was extermely amenable and won the hearts of those who knew her through the estimable qualities she displayed."

During François' reign and under his strong, directly exerted personal influence, the court and the nation took on the spirit for which they were famed in after years, and is essentially Gallic. The transformation of outlook and of manners upon the King's immediate circle rapidly spread through the upper classes, then filtered down to the bourgeoisie. Replacing her sister who formerly had follwed court and camp as a paid panderer to kingly pleasure, The New Woman won her way as a lady, with mind and will of her own, on a social footing with gentlemen, councilors and veterans of the field of battle. Elegance, distinction, wit and gallantry flowered in her path, and literature, art and that whole movement of the homan mind which we know as the Renaissance were to be her debtors.

Louise, prototype of the New Woman, had made François what he was, and François was to advance the New Woman and her cause by giving them a standing at court. François founded and naturalized the cour des dames; and tourney, ball and masquerade were soon aglow with beautiful and their gorgeous costumes. If the ladies could not afford costumes gorgeous enough, His Majesty would kindly help them out. Brantôme observed that the "court" was not where the King's person was but where then Queen and her ladies kept their state.

This new relation between sexes lay, chiefly, in a new attitude toward the fact of love, whether love be taken in the deeper-rooted, more enduring or in a lighter, more transient sense. Henceforward, a woman was to be no longer socially damned, if she chose to give herself outside the recognized bonds. Did not the possession of a mind imply the right to dispose of her body? It was a manner of reversion to the doctrine of the trouvère, who taught that love and marriage, marriage being what it was, were two different things.

Under Marguerite's influence, François collected the leading intellectuals of the kingdom, such as: Guillaume Petit, as his confessor; Guillaume Cop, as his physician; and Guilliaume Budé, a Gallic Erasmus, father of the French Renaissance. These men, largely due to their assiduous study of Greek, incurred the enmity of the Sorbonne and its professors; and between them and the enemy, for the next decade or two, François and Marguerite interposed as powerful protectors.

Feminity and scholarship dominated. The brother and sister were now keeping a real, no longer a play court, and the true Queen of France was not poor, homely, limping Claude, but the sparkling Duchess of Alençon, the Queen of Navarre. (A possible appeal to Esther.)

The indifference of Françcis I. with regard to the political fortunes of his brother-in-law, notwithstanding the numerous and signal services the latter had rendered him, disgusted the young prince, and he resolved to quit the court, where Montmorency, Brion, and several other persons, his declared enemies, were in the ascendant. He put his design into execution in 1529, after the conclusion of the treaty of Cambrai, and Margaret retired with him to Béarn, where she diligently applied herself, in conjunction with her husband, to all measures capable of raising their dominions to a more flourishing condition, as we learn from Hilarion de la Coste. "This country," he says, "naturally good and fruitful, but lying in a bad state, uncultivated and barren, through the negligence of its inhabitants, quickly changed its face by their management. They invited husbandmen out of all the provinces of France, who occupied, improved, and fertilized the lands; they caused the towns to be adorned and fortified; houses and castles to be built, that of Pau among others, with the finest gardens which were then in Europe. After having fitted up a handsome place of residence, they gave orders about laws and good government; they established, for the differences of their subjects, a court to determine them without appeal; and they reformed the common law of Oléron, which was used in that country, and which, since its last reformation in 1288, had been greatly corrupted. By their conversation and court they greatly civilized the people. And to guard themselves against a new usurpation from Spain, they covered themselves with Navarrins, a town upon one of the Gaves, which they fortified with strong ramparts, bastions, and half-moons, according to the art then in use." "This," says Bayle, "is one of the finest encomiums that could be bestowed on the Queen of Navarre."

Judging from several original portraits of Margaret which are preserved in the libraries of France, her last editors infer that her beauty, so much celebrated by the poets of her time, consisted chiefly in the dignity of her deportment, and the sweet and cheerful expression of her countenance. Her eyes, nose, and mouth were large. She retained no marks of the smallpox with which she was attacked before middle age, and she preserved the freshness of her complexion to a late period. Like her brother, to whom she bore a strong likeness, she was tall and stately; but her imposing air was tempered by extreme affability and a merry humor. Her enthusiastic panegyrist, Sainte Marthe, says of her, "Seeing her humanely receive everybody, refuse none, and patiently listen to each, thou wouldst have promised thyself an easy access to her; but if she cast her eyes on thee, there was in her face I know not what divinity, that would have so confounded thee, that thou wouldst have been unable, I do not say to walk one step, but even to stir one foot to approach her." Though conforming on special occasions to her brother's sumptuous tastes, Margaret's personal habits were remarkably simple. She dressed plainly, and after the loss of her infant son, almost always in black. Brantôme, speaking of the extravagant pomp displayed by Cæsar Borgia when he visited France, remarks, that the great Queen of Navarre never had more than "three sumpter mules and six for her litters, though she had three or four chariots for her ladies." Her biographers have generally asserted that this frugality was imposed on Margaret by the precarious state of her fortune; but it is rather to be attributed to her somber character and her munificent charity. The supposition that her means were inadequate to her rank is manifestly erroneous; for at the very time when they are said to have been lowest, we find her declining to receive from Henry II. payment of a considerable sum lent five-and-twenty years before to his predecessor in a moment of financial difficulty, and desiring that the amount should be given to the sisters of her first husband, the Duke d'Alençon.

Margaret extended her protection both to men of artistic and scholarly genius and to advocates of doctrinal and disciplinary reform within the church. François Rabelais, Clément Marot, Bonaventure Des Périers, and Étienne Dolet were all in her circle. Her personal religious inclinations tended toward a sort of mystical pietism, but she was also influenced by the Humanists Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples and Guillaume Briçonnet, who saw St. Paul's Epistles as a primary source of Christian doctrine. Although Margaret espoused reform within the Catholic Church, she was not a Calvinist, and her relations with her daughter were therefore strained. She did, however, do her best to protect the Reformers and dissuaded Françis I from intolerant measures as long as she could. In the end, however, as persecution by the crown increased, she was unable to save Des Périers, Dolet, or Marot. (Later painting.)

Her first and only son, Jean, was born in Blois in July, 1530, when Marguerite was 38, middle-aged if not already old by 16th century standards. But the child died on Christmas Day the same year. Scholars believe that her grief motivated writing her most controverial work, Miroir de l'âme pécheresse (1531; trans. by the future Queen Elizabeth I of England as A Godly Meditation of the Soul, 1548). The Sorbonne condemned this as heresy. A monk said Marguerite shoul dbe sewn into a sack and thrown into the Seine. Students at the Collge of Navarre satirized her in a play as ä fury from Hell". But her brother forced the dropping of the charge and an apology from the Sorbonne.

Marguerite turned more and more to her scholars. She could not spend as much time at her brother's court as before; this was because her husband, who possessed huge tracts of south-western France, kept his own court at Pau or at Nerac in Armagnac. Nevertheless, the bond between brother and sister remained as strong as ever.

In 1531 the Sorbonne made an embarrassing blunder. A book of Marguerite's devotional verse, Miroir de l'âme pécheresse ("Mirror of the Sinful Soul"), was placed on the list of of forbidden works. Unfortunately its author proved to be Marguerite, who complained to her brother. Alarmed, the Sorbonne explained that the book had only been condemned because it had not received authorization from the Faculty of Theology. It withrew its censure publicly, declaring that the book contained nothing but good. This incident lost the Sorbonne its privilege of authorizing works of theology.

In 1534, disturbed by his attacks upon the French throne and the monarchs of Navarre, Marguerite sought removal of Bishop Érard de Grossoles, in the see of Condom [sic] om Béarn. Threats were made toward Marguerite's life, which were not taken seriously. But horlty before Christmans, 1541, when Marguerite was again pregnant, and François I was celebrating a new heir, rumors flourished of a plot to kill Marguerite on Christmas Day by poisoned incense. She only went to Mass celebrated in her castle. Arrests were made, depositions taken, confession signed by one prisoner. But Marguerite's letters to François show that again she had asked for mercy, even for those seekng to harm her. The guilty names were never published. And Marguerite miscarried.

Marguerite continued working on her poems, to be published as Les Marguerites de la Marguerite, and her book of stories which she began in 1542. Apparently Marguerite paid little attention to the details of the publishing of her works so that the titles of most of her poems were slected by an editor at the time of publication.

As always, Marguerite was suspected of heresy. She was too prone to ridicule priests and friars, to scoff at superstitious devotions, and too fond of mystical piety.

On 31 March 1547 François I, King of France, died and when the doctors opened his body they found an abscess in the stomach, his kidneys shrivelled, his entrails putrefied, his throat corroded, and one of his lungs in shreds.

"In his last sickness," says Brantôme, "I have heard that she spoke to this purpose: 'Should the courier who brings me news of the king my brother's recovery, be he ever so tired, harassed, mud-spattered and dirty, I would embrace and kiss him as the finest prince and gentleman of France; and should he want a bed and not be able to find one to repose himself, I would give him mine, and gladly lie on the ground for sake of the good news he brought.'"

Marguerite had not seen her brother since February 1546. She had been staying in Navarre, tired and disillusioned, grieving for many friends. The news of François's illness filled her with dread. She dreamt that his ghost appeared to her. No one dared tell her that he had died.

At last she met a mad nun who was in tears. "Why do you weep?" asked Marguerite. "Alas!" cried the nun, "I weep for your misfortune!" Then Marguerite knew that her brother was dead. "You have tried to hide the death of the King from me", she said reproachfully to her ladies, "but God has told me through the mouth of this mad woman."

The death in April, 1547, of that brother whom she had loved so much, to whose glory and welfare she had devoted her existence, was a heavy blow to Margaret.(OLDER MARGUERITE.)

She survived him but two years, and that brief remnant of her life was spent chiefly in seclusion and religious abstraction from the concerns of the world. Nevetheless, it is not correctly stated by a recent English writer, that during that period "no solicitations could induce the queen to emerge from her seclusion, or interest herself as formerly in literature or politics." In the very next paragraph the same writer contradicts this loose assertion, by saying that Margaret "often solaced her grief by composing elegies and plaintive songs on her misfortune." Besides this , it is certain that the Queen of Navarre was occupied but a few months before her death in the composition of her book of tales; for the 66th novel of her Heptameron recounts a ludicrous adventure which befell her daughter, Joanne d'Albret, and the Duke de Vendôme, shortly after their marriage in October, 1548. Margaret's health began to decline in the summer of the following year, and she expired at the château of Audos, in Bigorre, on the 21st of December, 1549, in her fifty-seventh year.

(One year after her death, was formed the Pléiad, under the instigation of two poets who had enjoued Marguerite's patronage, Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay. The two met in a Touraine inn in 1548 and discussed who to make French literature "classic". They won over four young poets -- Antoine de Baif, Remi Belleau, Ettienne Jodelle, and Ponthus de Thyard -- and the scholar Jean Dorat, whose lectures on lyric Greek poets at the Collège de France and Collège Coqueret attracted entusiatic listeners. Calling themselves La Brigade, The seven attempted to raise the level of French literature by introducing into the French language words derived from Greek and Latin and by imitating many of the forms of classical literature. To evoke ancient practice, their poems were set to music in rhythms that reflected the poetic meters of the verse, by composers such as the Frenchman Claude Le Jeune. Influenced by the great 14th-century Italian poet Petrarch, the seven idealized in their poems the emotion of love. A hostile critic, noting their 7-ness, was reminded of the name given to a group of seven poets who flourished in the 3rd century BC at Alexandria, Egypt, including Apollonius of Rhodes, Callimachus, and Theocritus. The label "Pléiade" derived from the constellation commemorating the seven mythological daughters of Atlas and Plïone. The satiric label of this critic won them fame, and the term La Pléiade, for valued collections of literature, has persisted down to our time.)

Marguerite's only surviving child, Jeanne d'Albret, had been forced to marry the Duke of Cleves, despite piteous protests. The marriage took place on 13 July 1541 but, in 1546, was annulled.

The most important of Margaret's own literary works is the Heptaméron (published posthumously, 1558-59). It is constructed on the lines of Boccaccio's Decameron, consisting of 72 tales (out of a planned 100) told by a group of travellers delayed by a flood on their return from a Pyrenean spa. The stories, illustrating the triumphs of virtue, honour, and quick-wittedness, and the frustration of vice and hypocrisy, contain a strong element of satire directed against licentious and grasping monks and clerics.

Although some of Margaret's poetry was published during her lifetime, her best verse, including Le Navire, was not compiled until 1896, under the title of Les Dernières Poésies ("Last Poems").

If Marguerite d'Angoulême had lived longer, the terrible Saint Batholomew Massacre of Protestants in 1577, allowed by her nephew, King Henry II, might have been prevented. (Henry II said, "If it were not for my aunt, Marguerite, I should doubt the existence of as such a thing as perfect goodness on the earth.") Huguenots who escaped when to England -- such as Abraham de Moivre, who made possible the first annuity and created "the bell shape" curve credited to others. Paul Revere, American patriot, was descended from Huguenots who escaped to America.

DO YOU WISH TO SEE THE FRONTPAGE OF THIS FILE?