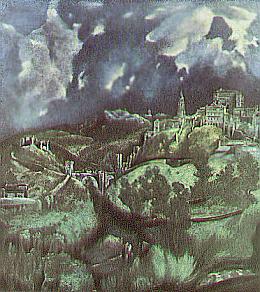

[The scanner distorted this, so it has been copied by one self-taught in a little Spanish, with "old eyes". Any errors, particularly errors of Spanish punctuation, are those of the copier and not of the original writer.]Whenever I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I went to see the magnificent canvas, "Vista de Toledo," painted in century XVI by El Greco, and every time it reveals something new, mysterious. Últimately, a study of the picaresque novel, Lazarillo de Tormes, has called my attention to this city of Toledo where lived the third master of Lazarillo, the famous knight's squire "well-dressed, his hair was combed, and he walked and looked like a real gentleman". The squire of the third chapter of the book could demonstrate to the duality of this "great city," in the words of Lazarillo. The outside of Toledo seems tranquil, but in fact it teems inside with the daily life of the market place; with the activities of the washer women washing together by the river; with the sufferings of poor men; and with the "adventures and adversities" of an orphan called Lazarillo who looks for food, a friend and love.

The painting of El Greco is surrealist and spiritual. The novel is realist, satírical, its hero leading us to observe what exists behind the lines drawn by El Greco.

We realize in the first page which of these are good people; "with help of some good people I ended up in this great city of Toledo ... they always gave me alms" (p. 147) Finding a new master, both walk about the town, "in places selling bread." (p. 149) They later pass through "the long and narrow street" (p. 164), that is delineated in the picture. They enter "a great church." Surely that is the same cathedral that stands out against that cloudy skies painted by the artist. Lazarillo mentions the people. El Greco paints a city without people, and we, the readers of Lazarillo, ask ourselves for the reason. What effect motivates the artist, converting to this so desert scene of life?

At the moment when the Toledo clock strikes one o'clock, the two new friends arrive at the house of the squire, the house which Lazarillo calls "the enchanted house" (p. 152)

Although we see that it has "neither chopping-block. nor bench, nor table", the squire with great ceremony removes a key from his sleeve to open the door. He asks if Lazarillo has clean hands. No matter that there is nothing to eat! Lazarillo says: "Sir, I am only a boy, and thank God I'm not too concerned with eating. I can tell you I was the lightest of eaters of all my friends, and all the masters I've ever had have praised me about that right up to now."

The inner hunger of the squire arises to the outside upon learnng that Lazarillo has some breadcrumbs! Then follows more worry, asking "if the bread were baked by clean hands." And Lazarillo is made anxious by the the ceremony of preparing the bed.

"I'll show you how this bed is made up. (156)..." He lay on the black bed. Lazarillo said, "And on top of that starving pad he put a cover of the same nature; I could never decide what the color was." (p. 157)

We learn two interesting facts about the city in this paragraph. "Many thieves wander at night," and "from place to place over great distances." Toledo has plenty of dangers and the center is far from the house of the squire. For that reason, it is better not to leave to look for food, and the squire advised, "as we were saying today, there's nothing in the world like eating moderately to live a long life." Lararillo was not very contented with these warnings of the squire.

On the morrow, the squire began to shake out and clean "his pants and jacket and coat and cape". Then he draws his sword from its "sheath", saying, "If you only knew what a prize this is!" He walked along. dressed well, "throwing the layer of his cape on his shoulder or under his arm. and with his right hand on his side, he went to the door", telling Lazarillo to watch after the house, make the bed, and get water from the river.

Could this river be the same one that we see in the painting of El Greco? Does this river provide for the daily life of the town? We see that this is so. This river edge is the same site where the washer-women congregate to talk and to work. And this is where Lazarillo goes to get water. El Greco paints spiritual water, that almost seems not to have a bottom; calm water, that does not move.

The poor men of Toledo suffer in this year of the novel, in the middle of century XVI, or, perhaps earlier (according to Otis Greene, in the year 1525), "In this town in this year no one ate abundantly" (p. 168). On page 179, we read that "since there had been a crop failure there that year, the town council decided to make all the beggars from other towns get out of the city. And they announced that from then on if they found one of them there, he'd be whipped. So the law went into effect, and four days after the announcement was given I saw a procession of beggars being led through the streets and whipped. And I got so scared that I didn't dare go out begging any more."

As we examine "the four streets" of the painting, we will be able to imagine these "exiles" leaving Toledo. Could it be that the foreigner, El Greco, has read this Chaper Three [of the novel] which describes these cruel events? Could this be why El Greco has painted that threatening sky and a city without life?

For, in the year of 1560, Kin Phillip II has suggested transferring the capital of Spain from Toledo to Madrid; and the citizens of Toledo, who in days past made this the center of tolerance of three religions, objected.

The boy being "a newcomer" does not dare to leave to look for food, but "I knew some ladies next door who spun cotton and made hats. They kept me alive". Thus, a scene reveals the sympathy of one poor man for another. Hungrily, beggars follow Lazarillo and its friend, the squire. In spite of this situation, the squire "would take a toothpick, of which there weren't many in the house, and go out the door picking teeth which didn't have anything between them." (p.181).

Cejador mentions lines from the Cancionero of Sebastián de Horozco demonstrating that our escudero is typical of others of that epoch,

"And the pretension is such That he has turned squire, with all its discomforts, Not having in his house six real [money]." "And also a poor squire Who lives always in misery." (Note 2, p, 178)The purpose of this very rich Chapter III [of novel, Lazarillo de Tormes] is, as we live our daily lives, to detail the daily life of one epoch of Toledo, experiencing with Lazarillo the indignity of being thrown of a house. The squire, fleeing from the reality, disappears, leaving the boy with the bailiff, the notary public and the people who demand possession of the house where the squire lived. Another reality behind the door."The View of Toledo" from the standpoint of Lazarillo de Tormes reveals truths that exist today in the twentieth century; realities of the poverty and the injustice unfortunately flourishing alongside the wealth and the comforts in many parts of the world of 1971.

Esther Odell Hays Zeta KappaThe Life of Lazarillo de Tormes, and His Fortunes and Adversities, Edition, Introductiom and Notes of Julio Cejador and Frauca. Madrid: Espaca-Culpa, S.A., 1969.Citations of page numbers are from the Edition of Burgos, published by Wife Calpe, in "Classicos Castellanos'.

See also: Green, Otis H., Spain and the Western Tradition, the Castilian Mind in Literature from the Cid to Calderon, Vol. I-iv, Madison and Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.